Recently, while reading through Leo Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, I noticed that the title character says in chapter 10, “What is this? Can it be that it is Death?” with Tolstoy telling his readers, amidst “unceasing agonies and in his loneliness… the inner voice answered: “Yes, it is Death.”

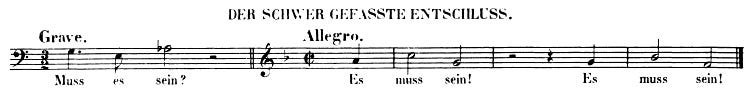

This reminded me of Ludwig van Beethoven, in his String Quartet in F, op. 135, where he wrestles with this concept in the fourth movement, the title translated into English as “the difficult resolution.” Beethoven employs two motivic ideas in this movement– the serious “Muss es sein?” (“Must it be?”) and the almost comical “Es muss sein!” (“It must be!”) as they answer each other while the piece progresses. According to K. M. Knittel, Beethoven used these two ideas to discuss his views on the reality of fate, yet in a way that truly says nothing about the truth in a concrete sense. Although there is no evidence that Beethoven’s motif was the direct inspiration for Tolstoy in this moment, these examples show that suffering is a given in our shared human experience.

The Grief of Death in Tolstoy

In The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Tolstoy implies that holy living is unattainable through suffering if someone lacks spiritual transformation. This is seen in Ilyich’s life before the illness and his life afterward. According to Leland Ryken, Ilyich is the premier example of a middle-class man “living life at the level of complete triviality and social convention.” Tolstoy depicts Ilyich as living the most average life possible, and brings this into focus at the beginning of chapter 2, calling out the “most ordinary” as the “most terrible.” He was born into a well-off family, agreeable, a lawyer as an occupation, and heralded as “strict in the fulfillment of what he considered to be his duty.” Yet, despite this, he is seen as discontent with his current state of life, consistently searching for higher levels of employment and monetary gain.

Through the course of the narrative, this search for fortune appears to bring momentary success, as he receives a role in the Department of Justice and begins moving into a new house, and feels “fifteen years younger” (Tolstoy, ch. 3) This all is tinged with an air of satirical “mockery” by the author, who contrasts this benevolent form of suffering with the suffering Ilyich feels later on in the story (Ryken, section 2). As Ilyich continues to live with the bruise received in chapter 3, his first response is to “force himself to think that he was better” by actively seeking out medical treatment.

However, “Es muss sein” for Tolstoy’s Ivan becomes “Death. Yes, death. And none…wishes to know it” (Tolstoy, ch. 5). Tolstoy makes the argument that all men consider themselves as immortal to some extent, as Ilyich argues in the narrative, death can “certainly not as applied to himself” (Tolstoy, ch. 6). This is heightened by the false sense of reality, or “death-denying culture” that surrounds Ivan, unwilling to believe that there is anything seriously wrong with the man (Ryken, section 3). Ilyich’s wife is the personification of this, as her kisses represent to him the life he used to live (Tolstoy, ch. 5), and the suffering of not understanding sickness and death (Ryken, section 3).

This new Ilyich grapples with the meaning of life as being “terrible loneliness, the cruelty of man, the cruelty of God, and the absence of God” (Tolstoy, ch. 9). “Muss es sein?” is brought back in the narrative, with Tolstoy like a composer developing and expanding onto the original motif, calling to God and saying “What is it for?... What do you want?” (Tolstoy, ch. 9). His childhood memories and his understanding of the forever-gone-away nature of innocence end with the realization that all is for death, or in Wattsian language, “Each pleasure hath its poison too, / And every sweet a snare.” The sweetness of the memories is captured in the terrifying thought that “The judge is coming, the judge!... What is this for?” as the motif superimposes this thought over itself again (Tolstoy, ch. 9). As the story concludes, “Es muss sein,” is transformed into “It is no more” as the “light” of the bleakness of death finally overtakes Ivan (Tolstoy, ch. 12). At the end of the story, Tolstoy leaves us feeling left and abandoned by the “inner voice” and God (Tolstoy, ch. 10).

The Difficult Resolution of Beethoven

“[W]e should not forget that it was Beethoven who wrote these notes— and at the end of his life. His last quartet,” Knittel writes. Around 60 years before Tolstoy wrote his story, Beethoven grappled with the idea of the inevitability of fate in his String Quartet in F, op. 135. One author, Gerald Silverman, suggested this motif had some ties to Handel and one Beethoven canon, which may signify Beethoven’s continuous grappling with this idea. The motif can be construed as an inversion of a motif from Handel— whether that is the case is not the point, however.

Beethoven begins this last movement with a declamation of the initial motif, and weaves it into a contrapuntal fabric, though that quickly is moved out of the picture for a rising and tense sequential motion of the initial “Muss es sein?” motif. Beethoven almost seems to be toying with the listener at the initial contrapuntal variation of the motif, as we expect an answer to appear as a fugue. Yet the composer interrupts this thought, and before we can get used to this initial motif, he brings in the second half, the “Es muss sein!” This happier and nonchalant expression has confused scholars, as Knittel notes (p. 44):

Unlike Kinderman, however, Cooper sees Op. 135 (and the alternative finale to Op. 130) as falling outside the norm of Beethoven's works. While Kinderman chooses to read 'humour' as one aspect of Beethoven's entire oeuvre, Cooper implies that it is, if not an aberration, then at least something new: the 'demons' have been 'exorcised'. Beethoven is heard to 'mock' his own 'dramatization of cosmic problems'… Cooper wants to hear Op. 135 as Beethoven's reconciliation with the world, his ability totranscend all its problems, producing a work that shows no signs of struggle: for him Op. 135 is not a Romance but a Comedy.

Hello! If you are enjoying this post, consider sharing it with your friends and family!

There are moments in the score where “Es muss sein?” can be elaborated as both happy, yet there are times Beethoven uses that motif to create harmonic tension, such as before the coda’s “poco adagio.” This could represent either the more philosophical approach— Beethoven throwing a wrench in the matter, “Why does the second motif have to be happy”— but his coda seems to resolve in that happy state. One area of note to me is the return of the fugual variation of the motif coming back at the second appearance of “Grave ma non troppo tratto,” amid the heaviness of dissonant tremolos, reminding me of Ilyich’s wife in Tolstoy’s narrative, who is constantly encouraging him in the falsehood of recovery for her own advantage, as Tolstoy shows us in chapter 5:

(“Why speak of it? She won’t understand,” he thought.)

And in truth she did not understand. She picked up the stand, lit his candle, and hurried away to see another visitor off. When she came back he still lay on his back, looking upwards.

“What is it? Do you feel worse?”

“Yes.”

She shook her head and sat down.

“Do you know, Jean, I think we must ask Leshchetitsky to come and see you here.”

This meant calling in the famous specialist, regardless of expense. He smiled malignantly and said “No.” She remained a little longer and then went up to him and kissed his forehead.

While she was kissing him he hated her from the bottom of his soul and with difficulty refrained from pushing her away.

“Good night. Please God you’ll sleep.”

“Yes.”

Does Beethoven truly say anything of significance with the interplay of these motifs, or is it as false of a reminder as the cheeriness of the ending of the piece? I think the answer may lie in the concept of “Muss es sein?” becoming “Es muss sein!” as Christopher Reynolds suggests. If the idea of Handelian inspiration is correct, this explains why it appears that the second motif is an inversion of the first, as a comparison between the second motif and a simplified version of what Silverman proposes becomes much clearer. The character that Beethoven appears to be portraying here is somebody who is indecisive, as the two motifs are truly just one, fighting over which perspective is ultimately right. This becomes “the difficult resolution—” grappling with how one motific idea could have two contradictory facets.

The Reversal of Perspective in Charles Wesley

Suffering and the reality of death is a concept that every Christian grapples with, as the Scriptures say “we have not here an abiding city, but we seek after the city which is to come” (Hebrews 13:14). Paul, in his letter to the Philippians says “to live is Christ, and to die is gain,” giving a grounded expectation in the hope of an eternal fellowship with our Creator (Philippians 1:21). This may be why Charles Wesley used the same motif, but in a very different way. “‘And Can It Be’ was written immediately after Charles Wesley’s conversion,” and presents the measure of the Gospel, redirecting the human-centered perspectives of Tolstoy and Beethoven to a perspective that focuses on the sufferings of Christ.

The beginning stanza begins with the line, “And can it be, that I should gain,” harkening us back to “Muss es sein?” and the dread caused by such a phrase. And Wesley does bring us some dread, as the stanza continues:

Died He for me— who caused His pain!

For me?— who Him to death pursued.

Wesley brings us the sufferings of Christ on full display, saying that Christ “bled for Adam’s helpless race,” “quenched the wrath of hostile heaven,” and was wounded so heavily that it would give us life. Yet amidst the “Must it be?” shines not a comical or submissive “It must be,” but the triumphant declaration, “Amazing love! How can it be

/ That thou, my God, shouldst die for me?”

“It must be so!” Wesley cries out with joy, as the “riddle” (Reynolds 184) of Beethoven is solved in the reality of the crucifixion of Jesus, and the void of death in Tolstoy is solved in the rays of “the dungeon flamed with light,” and the enduring hope that there “is… now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus, who walk not according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit” (Romans 8:1).

The idea that Ilyich reacted negatively against throughout the whole narrative is the answer to the “Must it be?” of both Beethoven and Tolstoy. “It must be,” Wesley says, not of our own griefs, but of the suffering of Christ, to reorient our perspectives. “The judge,” (Tolstoy, ch. 9) that Ilyich so dreadfully feared, should not be the cause for the Christian’s fear, as Wesley reverses the narrative in the last two lines of the poem. As we approach Good Friday, may this be the center of our hope— “Bold I approach th’ eternal throne / And claim the crown, through Christ, my own.”

Below is Wesley’s full hymn:

And can it be, that I should gain

An interest in the Saviour’s blood!

Died he for me?—Who caused his pain!

For me?—Who him to death pursued.

Amazing love! How can it be

That thou, my God, shouldst die for me?

’Tis myst’ry all! Th’ immortal dies!

Who can explore his strange design?

In vain the first-born seraph tries

To sound the depths of love divine.

’Tis mercy all! Let earth adore;

Let angel minds enquire no more.He left his Father’s throne above,

(So free, so infinite his grace!)

Emptied himself of all but love,

And bled for Adam’s helpless race:

’Tis mercy all, immense and free!

For O my God! It found out me!Long my imprisoned spirit lay,

Fast bound in sin and nature’s night:

Thine eye diffused a quickening ray;

I woke; the dungeon flamed with light;

My chains fell off, my heart was free,

I rose, went forth, and followed thee.Still the small inward voice I hear,

That whispers all my sins forgiv’n;

Still the atoning blood is near,

That quench’d the wrath of hostile heav’n:

I feel the life his wounds impart;

I feel my Saviour in my heart.No condemnation now I dread,

Jesus, and all in him, is mine:

Alive in him, my living head,

And clothed in righteousness divine,

Bold I approach th’ eternal throne,

And claim the crown, through Christ, my own.

Beethoven, Ludwig van. “String Quartet No. 16 in F Major,” 1826. Universal Editions, 1920. Reprinted by Edwin F. Kalmus, 1937. IMSLP, imslp.org/wiki/String_Quartet_No.16,_Op.135_(Beethoven,_Ludwig_van).

Knittel, K. M. “‘Late’, Last, and Least: On Being Beethoven’s Quartet in F Major, Op. 135.” Music & Letters, vol. 87, no. 1, 2006, pp. 16–51. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3526413.

Reynolds, Christopher. “The Representational Impulse in Late Beethoven, II: String Quartet in F Major, Op. 135.” Acta Musicologica, vol. 60, no. 2, 1988, pp. 180–94. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/932790.

Ryken, Leland. “Christian Guides to the Classics: The Death of Ivan Ilych.” The Gospel Coalition, https://www.thegospelcoalition.org/course/christian-guides-classics-death-ivan-ilych/#introduction-and-chapter-1-life-without-meaning.

Silverman, Gerald. “New Light, but Also More Confusion, on ‘Es Muss Sein.’” The Musical Times, vol. 144, no. 1884, 2003, pp. 51–53. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/3650701.

Tolstoy, Leo. “The Death of Ivan Ilych,” “The Death of Ivan Ilich”: An Electronic Study Edition of the Russian Text. Translated by Lousie Maude and Aylmer Maude, edited by Gary R. Jahn. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing, 2020. Open.lib.umn.edu, https://open.lib.umn.edu/ivanilich/.

Watts, Isaac. “Love to the Creatures is Dangerous.” Hymnary, https://hymnary.org/text/how_vain_are_all_things_here_below.

Wesley, John. Hymns and sacred poems, 1739. https://archive.org/details/bim_eighteenth-century_hymns-and-sacred-poems-_wesley-john_1739_0/page/118/mode/2up.

https://divinity.duke.edu/sites/default/files/documents/04_Hymns_and_Sacred_Poems_%281739%29.pdf

Excellent article. Very interesting to draw the correlations between the similar themes across the different works.